Learning An Impossible Form Of Exercise

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Jessica Ching |

| Related tools | Continuous Glucose Monitor |

| Related topics | Metabolism, Blood glucose tracking, Food tracking, Medication habits |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2018/09/23 |

| Event name | 2018 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | Learning-an-impossible-form-of-exercise.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

Learning An Impossible Form Of Exercise is a Show & Tell talk by Jessica Ching that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2018/09/23 and is about Metabolism, Blood glucose tracking, Food tracking, and Medication habits.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

Exercising without food for a person with diabetes is akin to scuba diving without air; medical “experts” say it’s impossible. Jessica Ching was unwilling to believe this and conducted a series of personal trials. She has since run thousands of miles, almost all without eating.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

Hi everyone. Thanks for coming to my talk. I’m really excited to be here. This is something that I’ve been doing for a while, and I’ve called my talk Scuba Diving Without Air because I’m going to be talking about something which is considered medically and physiologically impossible and personally, I love to hear that.

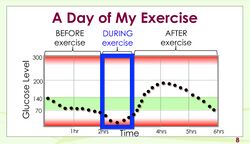

Which of these things are impossible? Scuba diving without air, flying without wings running without food? If you have type I diabetes like me all three of these things are considered impossible. So just a snippet on diabetes. I have type I diabetes, which means my pancreas which is the organ that makes insulin does not work at all. My body makes no insulin, it never will and as a result I have to manually operate and control my body. Now, this is a little bit different from type II diabetes which you might know about because it’s much more common. Type II diabetes is simply an impairment, but I have type I which mean that I’m doing this all the time. Now, this equation of impossible actually has changed a bit in the last few years with an amazing piece of technology that some of you are familiar with. Continuous Glucose Monitoring or CGM. It’s a breakthrough tool that I wear 24/7 and how it operates is there’s a little sensor on my stomach which beams to my phone, and you can see the screen capture here, gives me a reading live of my blood sugar every five minutes. I can see a lot. And the key thing that you want to take a look at here is that dotted line. This is what I live and die by literally. So, you’ve probably figured out that the dotted line is actually my blood sugar reading. I also call it my tightrope, and this is what I do every day to balance on the tightrope. So in order to keep that tightrope straight, I have to manage the three legs under the table. The three primary legs anyway which are food, insulin and exercise. Now, with type I diabetes in order to keep that tightrope straight every time you change one leg under the table you have to adjust the height of the others. And in this case, my talk today is about exercise, so this is why you’ll see that shoe level going up. So when I in this case have run for an hour at about 70% heart rate, I’ve found that I need to eat about 60 to 65 grams of carbohydrates to equal out my tightrope. Essentially, I have to eat all of those calories back. I get no gain. I eat them all back. And this is pretty lousy, and you can see why this effort is, because if you added this up it’s about with the amount I run, three times a week or so, four times, it’s about 5,000 calories a month worth or what equates to almost 20 pounds a year. It really, really sucks. So my experiment here and what I’m talking about today is the Holy Grail, which is, how can I do this? How can I raise one of the legs on the table under my tightrope and completely leave the other one at ground level? Now, technically this is impossible and in fact, all of the research literature that has been published on this, all of the research trials you will see that this actually is considered impossible. But I question them. I started to do some experiments, and this is over a course of many years. You remember that screen capture that I told you, this is essentially that screen capture with a few things superimposed over it. First of all is my green zone, which is my normal zone. In this case it’s 70 to 140mg/dl. That’s where I want to stay. That’s where I always target. You can see on either side of that green zone is a red zone. Red zones are bad. If you fall off the tightrope and land in one of those red zones it can be bad and sometimes when it’s really bad, you will not come back. You will die. So, this is a day of my exercise and you can clearly see as a person with type I diabetes that tightrope is not straight, especially with exercise. Essentially, it’s a wildcard. So, I’ve broken exercise up into three time periods which is before, during, which is indicated in the blue rectangle up there and after. And this was a typical run for me. I would come in before exercise, hopefully more or less in my green zone. Somewhere during exercise, I would drop somewhat and have to eat back my calories. And then I would come out and I would basically be okay until an hour later when I would spike up and then three or four hours later, which you can see I was headed for the red zone again. So, this is not ideal obviously, and it led me to say that I need to have a plan of such a method for doing this. I really need to deconstruct my experiments so that I can reconstruct them and control every variable. So here’s the first three trial that I did, and again, these are actual screen captures of my results with the red and green zones superimposed. So on the very top, I took just 40% of the food that I would have normally needed, 40% calories or carbs. I reduced insulin by 80% and I did it with half an hour lead time. You can see what happened. Red zone crash, and the reason there’s no more dots after that is I had to quit running. Second experiment or second set of experiments, I tried a different combination with more lead time, a little more food and it was better, but you can see what happened afterward. Way, way out of the red zone. So then I tried back to a little bit of lead time but a lot of food. So, on the bottom you see that’s pretty good. But the caveat was I had to eat back 60% of my calories. Not doing that. So I considered all to be unsuccessful trials. Later, I then realized I need to isolate. So, what I did was as you can see the apple in each of these I at zero percent. Not a single gram of carbohydrates. Insulin reduction was at exactly 80%. Exercise was at exactly an hour or at around 70 to 80% heart rate. The key determining variable, my hypothesis was lead time was insulin. So, the first time I tried 45 minutes in advance, I ate nothing and red zone crash. This is a typical pattern you can see. So, then I said well this is pretty bad, let me double that amount of lead time. So, I went to an hour and a half lead time. So, I almost hit the red zone, but I came way up after. I think I was headed for the north side red zone which is still not good. The rid one, I decided to try a two-hour lead time. This is a little bit out of conventional thinking because insulin starts to work about an hour to an hour and a half after injected, so this is well into the does it work time zone, but I tried it anyway. And you can see it’s not bad. Not bad, but I still was a little bit lower during the exercise period that I would like. Anytime that you drop out of that green zone at the bottom you lose energy and that’s not good for running. So, then I decided, you know, 10 minutes, does that make a difference. Fifteen minutes. So I did a 2.25 hour lead time, no food, running for an hour and there you go. The perfectly balanced tightrope. The physiological impossible feat. Now, it was so good that I thought maybe I could find something else even better, and I actually tried it again with a number of trials longer than 2.25 hours and you can see the results there. Not nearly as good. So using this formula, I have run half marathons. In 14 or so years I did about a race a year. I did almost 9,000 miles. I saved hundreds of thousands of calories. Had I had to eat back all of those calories I would have literally gained 249 pounds. Yeah. By the way, this formula that’s obviously customized for me, but I have applied this basic formula for others with type I diabetes with just some minor tweaks and it does work. So, the takeaways that I wanted to talk about this, my finisher medals here and I’m very proud of that. I actually dug them out of the garage to take this photo is that key factors are everywhere. And one of the slides you saw, the three legs, food, insulin and exercise there are all kinds of things. There are changes in my metabolism, do the daylight savings, stress and all that. But you have to identify all of them and figure out what all the major ones are. In addition, look at the variables and this is a big lesson. Because even that I knew what my variables were, somebody said something about the world view, my worldview is that the variables would likely be in a window of around 45 minutes to an hour and a half. And actually, the key variables was 15 minutes and 2.25 hours, both way under and way over of what I thought the possibility was going to be. This is why I believe actually that the research trials fail because they didn’t do it a thousand enough times. They did it you know, twice or three or five times and oftentimes the repetition and a trial of n equals one is very powerful if you keep doing it and doing it. Also, when I looked at my data, you know, my glucose monitor collects data every five minutes, 288 readings a day, 10,000 readings a year. I think I get a million readings every decade. Data speaks multiple languages and it is the way you look at the data. So for a long time I was looking a the averages of what my glucose ranges were, but when I looked at the distribution of that it was very different, and it actually leads me to isolate that key variable of timing. And last, it’s a challenge of what you know. What I have done here is considered physiologically and metabolically impossible by the experts in the field of endocrinology and diabetes. Many doctors have told me that I would be walking on water if I can do this, and this is why I made my talk the way it is. But by doing all these things and self-experimentation and analyzing data, I found that the world is not flat and that I can run without food.

Thank you.

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Jessica Ching gave this talk.