My Biological Rhythms In Sickness And In Health

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Azure Grant |

| Related tools | EEG (Electroencephalography), blood glucose monitor, EKG, iButtons |

| Related topics | Heart rate, Stomach activity, Blood glucose tracking |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2018/09/22 |

| Event name | 2018 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | My-biological-rhythms-in-sickness-and-in-health.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

My Biological Rhythms In Sickness And In Health is a Show & Tell talk by Azure Grant that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2018/09/22 and is about Heart rate, Stomach activity, and Blood glucose tracking.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

Azure Grant is interested in circadian and ultradian rhythms. Over a 10-day period she collected EEG, EKG, EGG, glucose levels, and body temperature measurements to explore how these different systems interacted.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

Azure Grant

My Biological Rhythms in Sickness and in Health

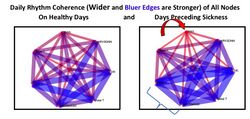

So, my name is Azure Grant. I’m a graduate student at UC Berkeley and this is one of my favorite self-tracking projects so far. So, it combines a couple of my core interests, one of which is the coordination of these things called circadian rhythms which are indigenous, 24-hour oscillations in activity outputs of the body. And the other interest is these faster within a day rhythm, things like your sleep cycle at night where your heart rate might go up and down several times or if you get hungry a few times a day. And what I wanted to do here was try to make a healthy base line map within myself of measuring many of these things at once as I could. So unfortunately, because it’s been fairly recently sensor technology that can do continuous monitoring of multiple outputs in the same person over several days, there aren’t really good maps of how many biological rhythms interact within a single person at multiple timescales for a long time. So, what I’m showing you here is the first device I wore was a Silhouette. It looks a little bit like an octopus taped to one’s stomach, but it’ an electro way that measures stomach activity as well as activity of the heart. So, heart rate and two kinds of heart rate variability built by this brilliant guy and friend, Armand Gharibans at UCSD for his engineering PhD. I also wore three body temperature sensors at the wrist, abdomen and core, as well as a Freestyle Libre continuous glucose monitor, and of course a log of everything that I did. And then as soon as I finished this a range got thrown into my project, which was I collected eight days of happy baseline data and as soon as I took all my devices off within a few hours I was super sick. And I think you’d maybe something in my data would show this transition from being healthy to being really sick. And so, this is just an example of a single output of the things that I collected over eight days. At the black line you’re looking at the distal temperature. You can see it goes up and down each day, and the blue outline is just for your reference is called the envelope of the signal, a sort of a proxy for its range. And what I want you to notice and what I had seen when I first looked at this is it looks fairly regular over the first four days. So, it sort of goes up to the same point and goes down to the same point. But then, over the last four days you can see this compression in the range of the signal, and I thought maybe this was something that would carry across multiple signals in my body and maybe this would tell me that I’m getting sick. So, I’m going to try to distil a lot of detail into if a few figures, because basically all of the outputs that I looked at had some sort of major disruption or shift in the way that they looked over those last four days that I recorded, whereas they looked fairly regular in the first four. And the way that I’m going to condense this and try to convince you that this was a change is via these plots. So, what you’re looking at are little graphs, where each one of those dots with a label that I hope you can read represents one of the outputs that I measured. So, at the very top that’s EGG for Electrogastrogram of my stomach activity. In the middle is glucose, on the bottom right is the distal temperature and etc. And so, each one of those dots is outputs daily rhythm oscillation, and the connection between them represents the measurement of coordination of their activity. So, if they were you know oscillating in a stable relationship to one another they would have a strong connection, meaning a wide edge and also a bluer edge. So, narrow and red edges are very weak connections. And you can see that the left side is the days that I was healthy, so an average of those first four days. The right side was me being sick. And a couple of things stood out to me here. One being, at the top of the right-hand plot, all of the connections to my stomach activity got much weaker on those days leading up to sickness. It wasn’t the truth in every single output from edges like between my core temperature and HRV got stronger. I also decided to try to look at this within those faster rhythms, and the first thing that I noticed was that it looked like absolutely nothing when I first did the analysis. So, if you look at the plot at the top it’s sort of pink everywhere, and I wasn’t able to pull anything meaningful from it until I took into account an important physiological aspect of these rhythms, which is that they happen around 3 to 4 hours per day while one is awake, and they happen around 1 to 2 hours while one is asleep. So, it wasn’t until I was able to separate those relevant periodicities of rhythm, as well as separating the waking data and the sleeping data that I was able to get this. So, at the top you are looking at plots of those faster rhythms network when I was healthy, and at the bottom while I was getting sick. And what stood out to me immediately was that the bottom graphs were way redder. So, it seems like without paying attention to any particular edge on its own that there was an overall weakening of my body’s internal faster rhythm network, only when I was starting to get sick. And so overall, I took a few things from this. I guess probably the most relevant one for like my future self-tracking would be that these weren’t changes that I could see or put together holistically with my I just by looking at the linear plot of each data output. There were just too many, like their worst 28 different para-wise combinations that I had to represent, and I couldn’t hold them in my head at once. But, once I started focusing on the relationship between the different outputs, and especially paying attention to the biological rhythm with each one of those I was able to pick out some particular features that were really suffering when I was getting sick. So, my stomach rhythm is totally going down to not being well organized with anything else, and overall, mis-organization of those faster rhythms within all of the outputs of my body. So, I have a lot more detail about this and if you have any questions about you know, how I did these calculations for what the falling apartness looks like in any of the other outputs. But my hope is to go back and to do this again and get a full eight days of healthy baseline without me getting sick and see how this all holds up.

So, thank you.

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Azure Grant gave this talk. The Show & Tell library lists the following links: