Blood Oxygen On Mt. Everest

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Fah Sathirapongsasuti |

| Related tools | Fitbit, iHealth Oximeter |

| Related topics | Travel, Metabolism, Heart rate, Cardiovascular, Sleep, Activity tracking, Personal microbiome |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2018/09/23 |

| Event name | 2018 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | Blood-oxygen-on-mt-everest.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

Blood Oxygen On Mt. Everest is a Show & Tell talk by Fah Sathirapongsasuti that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2018/09/23 and is about Travel, Metabolism, Heart rate, Cardiovascular, Sleep, Activity tracking, and Personal microbiome.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

Fah Sathirapongsasuti's project, carried out on his way up Mt. Everest, allowed him to carefully evaluate both the drop in his blood oxygenation and the effect of acclimatization—and contained some useful discoveries.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

About a year ago I went on a 10-day trek to Everest basecamp, and just to orientate yourself to what the trip looked like, it’s a 10-days there and back trip starting from a little town called Lukla, where we flew into, the most dangerous airport. Didn’t know that at the time. Survived it, and it’s a walk up along the Khumbu valley to the basecamp and down. And you can see here the gradual elevation gain all the way up and all the way down, seven days in, three days out.

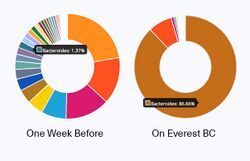

This is me on the first day. Pretty excited. So, Everest for the first time, pretty happy. But within a short few days just afterwards, you know walking up a little higher air becomes thin, the temperature drops, the land becomes arid, walking becomes hard and it got a bit in that time, but we finally made it to the base camp. As you can see here, Everest peeking out at the top, the base camp at the bottom corner is on the Glacier. And if you zoom in the yellow dots there, those are the camps that people camp out to prepare for summiting . Naturally, when you walk up to a height elevation you want to measure blood oxygen, so I bought myself a Pulse oximeter, got a Fitbit and didn’t really know how many times to measure. So I measured basically at all times of the day, after I wake up and when I go to bed, during the trip. And this is some data, so I plotted along the 10 days plus 2 days in Kathmandu I was there, at each of the elevations at each of the stops that I take to take a rest each day. On average, I walked about 11 miles per day on the way up and then a little more on the way down. But more importantly, the climb was pretty substantial, so I’ll be walking four Empire State buildings a day. You can see I walk a little less and I climbed a little less and less after I approached the highest point of Everest base camp, because walking becomes really hard at that point. My calories is about 3000 calories, 4000 calories, substantially more, especially substantially more that I took in. So, this is a pretty typical food that I’ll be eating. You know, a little of rice and a little thing of vegetables and a lot of the dhall bhatt, which is the lentil soup and the rice, and infinite refill apparently. So, but definitely not enough to fill the three or 4000 calories per day. At the end of it I lost about 6 pounds, because we have to weigh ourselves in and out on the plane. Another thing, and this is the blood oxygen part and it’s a little bit interesting. This is the oxygen in the air at different spots. So at Kathmandu it’s already 86%. At Everest it descends to about half of what it is, and this is my blood oxygen and unsurprisingly it dropped as I go further and further up. And 80%, here right now it will be about 99 or 100%. And if I drop to about 80% it will be concerning and I’d be wheeling into ER right now. And that’s basically, and I dropped actually at the lowest point it’s about 71%. And unsurprisingly that is when I actually experienced headaches and blurry vision, a pretty typical symptom of altitude sickness setting in at 80 and when I dropped below 80. And another kind of measure point there, the purple line, the number of times I wake up per hour per night. And the worst point is basically once an hour, and I’m not going to be talking about what happened in Kathmandu the last day. Now, another thing that kind of surprised me afterwards is kind of correlating all the data together, one thing, resting heart rate, people know that resting heart rate is a pretty good measure of overall health. I didn’t expect that going to be tracking my blood oxygen as well, so it seems to be measuring something there. The next thing is like the rest. So over most of the times of the day I’ll be walking pretty vigorously. But then the guide would tell us to take breaks and I was like nah, I don’t really need breaks you know and walk a little bit more. But then I take breaks and take measurement for 30 second increments and see that my blood oxygen actually increased quite substantially here in this plot is from 77 to 87. A 10 point difference, and that’s the difference between not feeling headaches and headaches, right. So a short break actually goes a long way, and I didn’t expect that. Now I come back and looking through this, and people know this. People know that at elevation when you exercise your blood oxygen can drop quite a lot, and that’s really not what happened here at sea level. So that’s kind of cool to see the reverse of that. And, it’s important to take breaks, especially there. The second thing and not a surprising observation, how does acclimatization work, and it’s real and it’s measurable. So, there’s this one town called Nameche that we stayed for three days, two nights, one day up and one day down. Throughout the three days, the longer I spend on the mountain, the higher my blood oxygen reads, and this is replicable at different time points of the day. One thing I wish I had done more is actually measuring blood oxygen of my Sherpa guide more consistently. You know, Sherpa is not only a job title for guides but also a clan, a genetic population that carry EPF mutation that allowed them to adapt to higher altitude and hold more oxygen in their blood. And as a few points I asked my guides to measure and anecdotely, I can see every single time without fail the number of V 4 to 5% higher than mine, so there’s definitely something there. And lastly as a hat off, to my friends, I did a biome for one week before going as a typical omnivore I have a pretty diverse gotten microbes and fairly healthy, but at this camp this is at genus level. So, 86% of my gut is occupied by different microbes, and it’s like zero percentile and virtually no one has ever seen this before. The good news is it came back. So three months after, I did it again and it actually could tell us more than in the first time, so we are quite resilient there. Right, a few things I learned, a more practical thing like and oximeter is pretty finicky especially when it’s cold. My fingers most of the time during the day would be cold and when there is bright light outside. So, the best time to be measuring this is right before bed or after waking up, and that’s the date I ended up using. And I wish I had done more with the local population to actually compare that and it would be more interesting.

I wrote a little blog on my companies website, and twitter me if you’re interested in reading more, and with that I’ll welcome any questions

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Fah Sathirapongsasuti gave this talk.