Does My Stomach Anticipate My Meals?

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Benjamin Smarr |

| Related tools | iButtons, Continuous electrogastrogram rig |

| Related topics | Genome and microbiome, Stomach activity, Temperature, Blood glucose tracking |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2018/09/23 |

| Event name | 2018 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | Does-my-stomach-anticipate-my-meals.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

Does My Stomach Anticipate My Meals? is a Show & Tell talk by Benjamin Smarr that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2018/09/23 and is about Genome and microbiome, Stomach activity, Temperature, and Blood glucose tracking.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

Benjamin Smarr has been collecting glucose, body temperature, heart rate, and stomach activity data to see how his body responds to scheduled meals, and whether it keeps the schedule when he fasts.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

My name is Ben Smarr and thanks for inviting me back. I’m a circadian biologist and physiologist at UC Berkeley, so this is the sort of stuff I think about anyway. We talk about all the ways that biological clocks regulate and function within us. I wanted to know if this is really something that affects how I'm eating and how my stomach is reacting to meals.

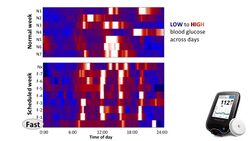

And the reason I'm addressing that question, in particular, is that earlier this year we published a new paper, showing an invention from Armen Gharibans, who’s an extraordinarily talented engineer down at UC San Diego who figured out a system for measuring continuous stomach contractions: electrogastrograms (EGG). If you see EGG, it’s not egg, it means my stomach. We found being able to listen to the stomach continuously, noninvasively, for the first time, all kinds of cool patterns appeared. We found that there’s stereotype reactions to meals. There’s also a component dependent upon on the time of day, likely modulated by the circadian clocks, and then also sleep time independent, you know differently but still modulated by sleep timing. So that’s cool. There’s all these different timing systems interacting with my stomach apparently. Does that mean that this is changing how my stomach is behaving across the day of the function when I’m eating? And wearing this thing, I think Azure described it as sort of like an octopus. You know, it’s a lot of stickers on you, so while I was going to do that for a week, I figured I’d pile on some other things too and just try to make a rich data set and examine them. The basic experimental paradigm was pretty straight forward. Just AB so far. We’ll go back and do AB again, but the A, this is a raster plot of when I’m eating across the week. So the way you reads this is we have from midnight one day until midnight the next day, and you can see that I’m asleep so there’s nothing going on. Then a bunch of ticks starts happening. That’s I’m eating through the day. Then it goes back to a flatline and that’s when I’m asleep again. And then each day is on top of the subsequent day so we’re working at a week here. That is then compared to a week during which I then regiment my eating, and I eat at the same time every day and I'm eating the same meals in every meal. And this is the real time of me logging my meals on my fitness tracker, so you can see that I kept to it pretty well. And then that last day is a day of fasting. The idea being if I’ve gotten my system really nice and lined up. And my stomach knows when to anticipate a meal because I’ve been doing this for a week now, will it look like it was anticipating a meal and I don’t give it any food to eat will it have a mind of its own. And very satisfyingly this seemed to be the case. So here now what we’re looking at is four days during that regimented week. We have fasting minus six, fasting minus three, fasting minus one and then fasting. And what you can see is that the blue is where I’m asleep. I haven’t put the device on. I wake up. I tape it on and the more it gets to white, the more active crunching my stomach is doing. You can see there’s a line at breakfast, there’s a line around lunch and then there’s a line at the end of the day with dinner. And especially around breakfast and midday, that really seems to show up in my stomach on this day of fasting when I haven’t given my stomach anything to do actually, but it just seems to be waking up and thinking it should be time to eat. So right there, that was really exciting to me because that seems to imply that when I’m eating during the day like my lunch probably how my body deals with that food has a lot to do with the phase which my stomach is. Whether my stomach was ready for food or not, anticipating food or not. Obviously, a lot more experiments to do to flesh that out, but really exciting confirmatory results from just me doing to on myself kind of a thing. But I had these other devices that were continuous. This I was only wearing periodically, and I have these little temperature sensors. I-buttons and I had a continuous glucose monitor on, a Freestyle Libre. And those individually, you know, you could definitely tell when I was during my regimented week or versus during my random week, but the day of fasting wasn’t super clear to me that something wasn’t coming through in those. Luckily though as I also start looking at relationships, I have to explore different mathematics to try to figure out how do we make sense of this data. And in using a single modality like my stomach wiggles, I was able to use a technique called dynamic time warping and just try to compare each day to the previous day and say what's the similarity across days that way. And the idea of time warping is you take one set of numbers right, like my fasting day and you say how much wiggling of my values do I have to do to get it to look like some other day. So here you can see the result of that is my fasting day really hasn’t much less wiggle distance from these days coming before fasting in this regimented week, than it does from these grey bars, which are these days from the unregulated week. Again, showing the shape of my stomachs activity across the day looks like what it was coming from, looks like there’s some momentum there. So how do we apply this across different modalities? In that case, we need a different way to visualize it. So here what we're looking at now is just sort of a cartoon schema that I made up. One of the things I learned through this project was we really need to spend a lot of time and thinking about how this data is visible. How do I make sense of it, how do I share it with people and that's not a solved problem any more than the biology is. So that’s really fun for me. Here we have nodes, little dots, which in this case are two sensors, one in the armpit, one on the wrist, axial and distance temperature and the continuous glucose. So the size of the dot will be how rhythmic did those look within a day, the ultradian ripples that we’re seeing in my stomach for example. And then the connection will be how much did those ripples if they're there seem to be coordinated. So how much was the distal temperature having a stable relationship with the wiggling in my axial temperature for example? And these are the real data, and what you can see is that on the inner circle that ultradian power and on the outer circle the day, so circadian power, and I think what’s pretty clear to me at least is that I know it gets washed out a little, it’s pretty clear, is when I’m eating when I just feel like it, I’m just living my life there’s not actually a ton of coordination. The oscillation strength of any given node, the white dots is pretty low, and you can see that the circles pretty sort of thin and red. Whereas where I compare it to this week where I’m on a schedule and my body knows what to anticipate all across my body, the coordination seems to go up pretty substantially. And that happens at different timescales, both across the day and within a day. Now on a day of fasting, that was less within a 24-hour period, so I can’t really talk about daily power, but we can see the ultradian level that within a day level it still looks nice and fat and blue. It still looks very much like the week of regimentation, similar to what we saw in the stomach. So that’s very encouraging to me going forward, that we really can during this self-exploration work start to make sense of things that you know, classic NISH funded science really hasn’t tackled yet. How do we look at time series within an individual so that we can think about things like coordination where, for example, Gary’s stomach and my stomach at any given moment are probably doing different things? So if we just take the average we’ll lose all of this. So that’s very exciting to me and it reinforces the discovery value for n of one stuff, it reinforces the idea that it’s fun to play with science and it helps me think about how do I visualize, how do I share things more as well as the science itself. And it helps me think about you know, how do I appreciate people building new toys that let me see the modality of my body. Freestyle Libre was new, the EGG was new, that’s really exciting right, it keeps wanting me to learn what are other people doing.

So that’s my story. If you want to contact me, you can reach me at this email, and thank you.

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Benjamin Smarr gave this talk. The Show & Tell library lists the following links: