Lies, Damn Lies, and Correlations

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Eric Jain |

| Related tools | Nike+ FuelBand |

| Related topics | Sleep, Sports and fitness, Heart rate, Activity tracking |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2013/10/10 |

| Event name | 2013 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | Lies-damn-lies-and-correlations.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

Lies, Damn Lies, and Correlations is a Show & Tell talk by Eric Jain that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2013/10/10 and is about Sleep, Sports and fitness, Heart rate, and Activity tracking.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

Eric Jain has been collecting a bunch of data including step counts, calories burned, sleep patterns, and more. He is interested in correlation and finding some external factors in the way how his body works. In this talk, Eric discusses his experiments and what he has learned from it.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

Eric Jain - Lies, Damn Lies, and Correlations

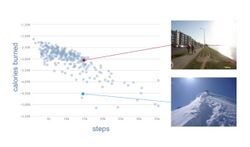

I looked on a startup in the Quantified Self area, but what is my personal interest in self-tracking. So for some people it’s just the fashionable thing to do, nothing wrong with that. For other people they may have specific goals they want to accomplish, they may do it for motivation, so that’s nice. I’m not terribly interested in that and I can’t just show off my data every time I give a talk, so my real interest is gaining insights, finding patterns, how does x influence y. So knowing how many steps I walked is that insight? Well, not really. Is knowing about certain trends like how is your weight changing, is that insight? Well, maybe. What I’m really interested in is correlations and finding out one variable and finding some external factor in the way how my body works. Now, when going and looking for these kind of effects there is going to be a kind of a sweet spot and things that we can practically look at. For example, there is no way I am going to be able to do an experiment that shows taking some extra vitamin D is going to reduce my personal cancer risk, right. On the other extreme, there’s going to be experiments like I don’t need to have Quantified Self and complicated tools to learn if I touch hot stuff it’s going to hurt. So to look at things that are manageable and just right. So one of these things is sleep. Sleep can get really complicated, but there is definitely a bunch of things that are really easy to track. So sleep of course we know all we expect that it influences your previous night sleep, so influence how well you sleep. We expect that how much you exercise will influence how you sleep, and then there is a bunch of other factors like what’s the room temperature, inequality, etc., in your bedroom that could influence how you sleep. So for recording sleep I don’t do anything terribly sophisticated. I just want to record how long did I sleep and roughly what percentage of time did I actually sleep and not just lie in bed. Now, I was quite dismayed that it does not appear to be any correlation at all between how long I sleep one night and how long I sleep the following night. So there is neither a statistically or practically significant difference here, so what do I mean by practically significant? I mean that there is a sizeable correlation or a large enough effect size that is statistically significant that I mean it’s not just random chance that you are finding this. So there is a whole bunch of different statistical methods to help you evaluate this. I don’t have time in my 15 second slides – even if I knew more about statistics. I don’t have enough time and I’ll just do the obligatory disclaimer about the correlation and causation here and leave it at that. So next I looked at tracking how active I am and does that influence sleep. So I am recording how many steps I walked, how many calories I actually burned. Now most of the exercise that I get is actually walking around, but interestingly enough, just counting steps won’t work for me because it turns out that whether I am walking around in town, or I am climbing up some mountain in deep snow, there is a huge huge difference in how much energy I expend. Now again, it turns out here. We don’t have a correlation between exercise and sleep either, so quite disappointing. There is a statistically significant correlation, but it is not meaningful because it is so small, so tough luck. So last I looked at I have a small weather station and I record a temperature and other variables, and I look at that how it correlates with sleep. Finally we get the correlation and that is the one interesting thing with correlations, that if you keep looking long enough you will find one. So here, finally, we can see that in fact, if it is colder in my bedroom up to a certain point I will be able to sleep better. So here is another thing that I was reading and got interested in how does doing really strenuous trips or exercises, how does that change your resting heart rate. So initially I thought that would be something lazy and I didn’t want to do complicated stuff, so initially I just did like simple pulse measurements by hand or with some apps, and I realised they can be really widely varying and even within the same minute I get values way off. So it turns out that I actually discovered that even within a minute, you can have huge variations in the timing between your heartbeat. So I went to the literature and I discovered I’m not the first person to notice. One common thing here that people have like sort of periodic variations, and this can be in all scales like in the example, here with the heartbeat the variations in the second and minute scales, but if you are looking at other phenomena’s it could be variations in weight over the scale of a month, or it could be seasonal variations. And for extra fun, of course, these different periodic variations can overlap and that is really complicated patterns. So here you probably can see anything, and basically I looked at days where I had a really long tough hike, and I can see the following day my resting heart rate goes way up and then it drops back to normal and slightly overcompensate. So not the breaking scientific discovery, but it is interesting to read about stuff and actually kind of reproduce it and see. Yes indeed, my body works this way too. You can see also that the heart rate is a bit elevated in the day that I go for the hike, and that is because I was woken up by an alarm clock and somehow I don’t like that. Also another thing to take into consideration when you are trying to reproducible measurements. This example, here can go in either direction and we have a common pattern that have changes. See have to be really careful about the timescale in which you are measuring, because you know if you are not measuring the long enough you will may be say there is a huge upward trend, but if you continued measuring, you will discover that there is actually nothing really happening in the long run, and you aren’t then back pretty much to normal. Or just in this case, where we change something, and initially for a while there could be pretty much no notable change, but perhaps maybe only after a few days, or if you weeks and suddenly there is a big impact. So my takeaway lessons that while you can expect like pulling in all of your data and run some of statistical procedures and discover all those amazing new correlations you not going to have a good time. In reality it’s more like you expect. You read about something and you have some expectations and you want to go back and test, and do I really see this correlation or not. And to be honest. Often you will and won’t be able to confirm this correlation, but it’s still useful.

So I am going to have an office hours tomorrow and I didn’t have the guts to publish all of my data, but it is openly available, if you want to have a look at my data, or maybe bring your own data tomorrow at 1:30 I think.

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Eric Jain gave this talk.