Seeing My Data In 3d

| Project Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Self researcher(s) | Stephen Cartwright |

| Related tools | calendar |

| Related topics | Productivity, Media, Location tracking |

Builds on project(s) |

|

| Has inspired | Projects (0) |

| Show and Tell Talk Infobox | |

|---|---|

| Featured image |

|

| Date | 2017/06/18 |

| Event name | 2017 QS Global Conference |

| Slides | Seeing-my-data-in-3d.pdf |

| This content was automatically imported. See here how to improve it if any information is missing or out outdated. |

Seeing My Data In 3d is a Show & Tell talk by Stephen Cartwright that has been imported from the Quantified Self Show & Tell library.The talk was given on 2017/06/18 and is about Productivity, Media, and Location tracking.

Description[edit | edit source]

A description of this project as introduced by Quantified Self follows:

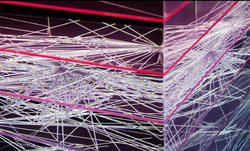

Stephen Cartwright has been tracking his family member's location for years. He tracks where they are everyday of the year. Stephen then makes glass, plastic, and resin sculptures that capture the beauty of the self-recorded data. The sculptures float in the air or are captured in clear blocks to reveal intersections and correlation of the data. In this video, Stephen shares how he does his work and what he learns from the process.

Video and transcript[edit | edit source]

A transcript of this talk is below:

Stephen Cartwright - Seeing My Data In 3D

I also have been working with tracking my family members, and they’ve been accommodating to this practice of mine. And so I tracked where they are everyday of the year, so they show me their calendar at the end of the year and I can track where they are. So this is a map of the family, but I started taking things out of numbers and drawing into the third dimension. And sometimes I like to visualize it like this. So this is I’m making a polygon with each member of my family as the vertex of the polygon, so therefore I can look at them and I can run this through time and I can see how that polygon changes shape as we go through the year. As my family travels, as they move, and that sort of thing, and so it makes me start to think about the data in a real sort of geometric kind of way, and really abstract way. And it really makes that geography that separates us really real and present. So when that polygon gets really big, the family is very very dispersed and we’re not sort of communicating very much. And then on very rare occasions that polygon will actually collapse down to a single point you know, at a wedding, or at a Christmas time when everybody is altogether at the same place. So for me you know, visualizing it, taking it slightly away from the math and start to thinking about it more geometrically informally gives me a whole different way of thinking about the information. So this is just the math again so you can it, but I’m sure a lot of you, you know you’re working with data and numbers all the time, and one of the easiest ways to deal with that is to graph it out. And I do that to, and that’s one of the first things that I do. It’s a really easy way to see what the data kind of looks like. But as an artist, one of the things that I like to do is sort of strip the scales away and start to think about those lines in a little bit more formal formally so they’re stripping the numbers away. And then I can take this line graph and stretch it out in space and sort of rotate it a little bit. I get to this stage, you know you can see each individual line and that what that makes is a very nice skeleton for me to start talking about how to make a three dimensional object. And so there’s the object sort of skinning over to make this data topography and this is what I base a lot of my work on this kind of topographic data scape that’s very unique to us and very specific to that kind of data. And it’s also very specific that I think about it as one very particular set of data among a very large possibility. So that square sort of represents the possibility, and the surface in the middle kind of represents the one specific thing I’m looking at right there. So like I said I’m a sculptor, so I decided I was really compelled with those kinds of shapes and I wanted to make them. And so this is one of the first ones I made. It’s made out of Plexiglas and I’ve C and C carved two halves of this surface and then poured colored resin into the middle. And then so I can see that sort of ephemeral floating dataset in the middle of that kind of solid block of material. And as I’ve done that I’ve gotten a little bit more precise in my working, and to me it really highlights that sort of duality of the data and of this thing. So it’s a very solid object. They are very heavy. This is about 15 kilos, but the surface in the middle seems very very light and it floats and it’s translucent. And that kind of to me is like the numbers that we’re looking at. So that numbers very specific, but the number can be very can change a lot, depending on what the context is. And so I really like to look at them in terms of that kind of duality of the data. and also in the way that they evoke different kinds of landscapes and the different kind of datasets that I’m deriving them from. Working with this method, it’s been really rewarding to start looking at multiple data sets together. So this is two different datasets and with the translucent layers of this ribbon of information you can see how they intersect and interact, and how they may crossover, correlate and what they can do. But I think one of the more important things about working in a sort of sculptural way with my data is that it changes your relationship with the data. We are very use to visualizing our things and maybe if we’re lucky or pre-skilled we can sling it around and zoom around and zoom out and turn around in a digital space. But once you bring something into the physical space then your body has a different relationship to it. So you have to move your body around to look and get the angle, and it makes the data that you’re visualizing become a more concrete, a more real kind of thing. And so because your interaction with it is so much different, you’re active as opposed to being passive. This is just where I can change the lighting on these objects and get different effects. It also makes the scratches show up really well, so. So moving back to the latitude and longitude project, I look at this piece. This is basically a timeline of that latitude and longer to project that’s been going on for 19 years. And I can think of this piece as a sort of a physical biofeedback object, where I can look at that timeline and I can see the exact moment, and you can probably see the exact moment too when I got a real job and had to settle down. So I think about the objects that I make that are derived from my life, and what they look like and what the objects are that I want – what I want my objects to look like in the future.

Thank you.

About the presenter[edit | edit source]

Stephen Cartwright gave this talk.